As many know, I purchased a 2022 Ioniq 5 SEL LR AWD in September. From a driving experience, it’s been such a huge upgrade that alone I would say I have zero regrets.

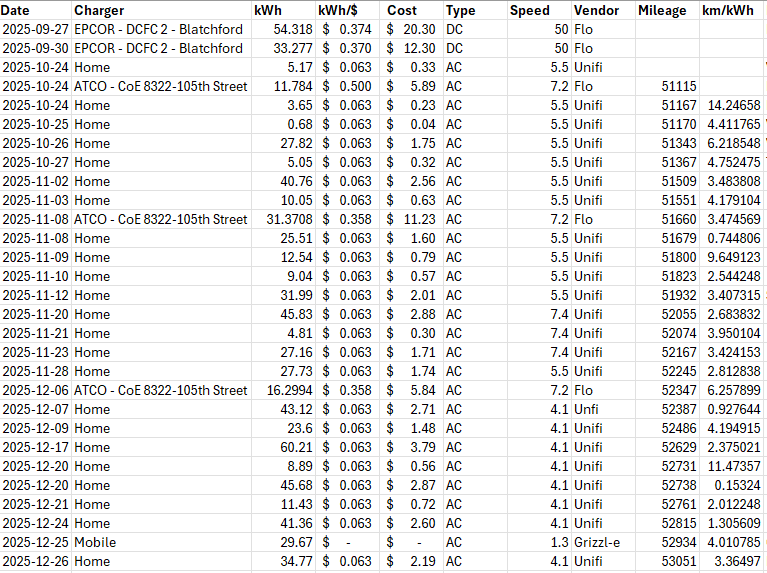

But many are going to ask – how much has it cost me, actually, to drive the car in the winter? I was curious too! So instead of theory, I ran the numbers on something better: my actual driving data.

Over the last three months, I have driven 1936 km in my Ioniq 5. It’s largely been urban driving, with a few excursions out of Edmonton.

So in summary:

– Distance driven: 1936 km

– Electricity used: 723.57 kWh

– Total cost: $86.96

– Average cost per km: 4.65c/km

Including:

– Cold-weather driving (nearly -30 °C)

– Highway trips

– DC fast charging (the expensive kind)

– AWD and winter tire losses

So, in other words, this is not a cherry-picked “summer, home-only charging” scenario. This is worst-case; it hurts my face to be outside, real-world data in the depths of an Alberta winter.

Keeping this fair, I benchmarked against actual Edmonton gas prices in 2025, using my old car, a 2015 Honda Accord Coupe 2.0L car, without winter tires, a very efficient car in its own right.

– Average 87 gasoline: $1.35/L

– Fuel economy: ~7.5L/100km combined

On a head-to-head comparison, over the same 1936km, the Ioniq 5 consumed $89.96 of “fuel”, at 4.65 cents per km.

The Accord, over the same 1936km, would have consumed $238.67 of fuel, at 10.1 cents per km.

This comes to approximately 10.1 5.45 cents/km in fuel costs.

That’s over a 50% reduction in travel costs alone.

This doesn’t account for the fact that I’d need to change the oil in the Accord, possibly the transmission fluid, replace the brake pads and/or rotors much sooner, and other maintenance related to the thousands of moving parts involved in making a gasoline engine work. It also doesn’t account for the fact that the Ioniq 5 has Blizzak winter tires mounted, while the EPA-rated Accord has summer tires. I am confident my 2026 summer numbers will be even more staggering.

We do need to have a little reality check here, though. In the extreme cold that we see here in Alberta, the in-town range is reduced. This is mainly because my trips around town are much shorter than when I leave town, but it is the same issue for gasoline-powered cars.

Once it’s warm, it’s pretty much gravy for both cars. The advantage here over a gasoline car is that, if the EV is still plugged in, it will heat the cabin using mains power (which we know is cheaper than gasoline) rather than the battery pack (as it always does otherwise), thereby protecting the EV’s range. This isn’t always possible, so the EV advantage in pre-heating the cabin is negligible, unless you can plug in at all your destinations.

To recap, these are worst-case numbers that rebut the idea that EVs don’t work in our climate. These numbers prove they do – and still save over 50%, even without factoring in gasoline engine maintenance costs and the EV having high-drag winter tires.

I’m going to continue to gather data through 2026 and look forward to reporting back next December.